When a Karen Iris Tucker, a reporter for the village voice contacted me about the Brooklyn Industries vandalism, I had no idea this was a cover story. For some reason I thought this was going to be a tiny blurb and that there was such a short deadline that it may never happen at all. Surprise. Seems like the whole broken windows theory of journalism. If it bleeds it leads, right? When Starbucks windows got broken at the WTO in Seattle, all the media attention focused on Anarchism and property destruction, not on the fact that hundreds of thousands of people organized against free trade. In fact that has become the mantra for the establishment's harsh tactics towards all demonstrations since November 1999 and of course September 11th. The theory goes something like: Because 20 or so anarchists from Eugene Oregon, targeted a few corporations lavishing in the rewards of a globalized economy, therefore we must take your civil rights away, shoot at you with "non-lethal" weapons and pre-emptively lock up every suspicious character at every Trade demonstration since. Same theory with the critical mass, that the police still use today in court. The ride was fine, until it was taken over by those ANARCHISTS. This justifies their violent attacks on bike riders. So now we look at the front page of the village voice and there is a anarchy symbol made out of bike parts and a huge photo in the middle of a masked rider with a paper bag over his head. I'm sure the cops now have more fuel for their fire in demonizing our bike rides as they connect the dots in some sadistic way to justify ramming us with their mopeds, but it would be nice to connect our own dots towards a more positive light. Such as how tall bikes and mutant bike gangs get people excited about riding their bikes and about making things out of discarded materials and about making our own culture instead of having it spoon feed to us by clothing companies. Its important to note that both DKNY and Bergdorf Goodman have had bikes displayed in their windows in the last couple of weeks. This may not mean that bike culture is for sale but it does mean it is popular and not to mention fashionable. I mean we all know bikes make an excellent assesory with your $500 Dolce and Gabana handbag. I still think it was a harsh lesson for Brooklyn Industries to learn that mutant bikes are a cherished cultural icon unlike the Bad Brains logo which can easily be transformed into selling the word Brooklyn, displayed on one of their many t-shirts. It was a bad choice of window display mainly because Recycle-a-bicycle doesn't get kids to make those kind of bikes. So there's an article in the NY Times and one in the village voice, can we move on now? Maybe we could focus on some more minute issues like why the fuck are we in our third year in Iraq? I am grateful for the plugs for my blog in both the Times and the voice. I do need to make one correction from the voice article. I did not make my tall bike for C.H.U.N.K. Chunk members helped me make a tallbike for me and I am even more grateful for their help cause that was a life long dream. Thanks to the Smeltor for doing the welding. Hey, when are those CHUNK group rides in NYC? let me know, I want to wear a paper bag over my head and bring my DKNY bad brains t-shirt.

village voice articleMutant Bike Gangs of New York

Tall-bike clubs live free, ride high, and don't want your stinking logo

by Karen Iris Tucker

March 21st, 2006

The Black Label Bicycle Club is virulently anti-consumerist; its riders recycle everything from bike parts to vegetables. They pick through dumpsters for communal vegan meals. And they don’t (usually) talk to the press.

photo: Ray Lewis/fleabilly@mac.com

Article:

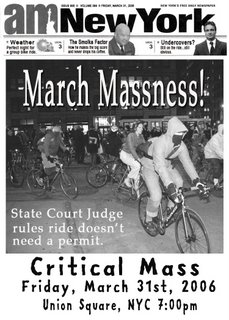

They were meant to be edgy advertising, those tall bikes towering in Brooklyn Industries windows, but somebody—or somebodies—took their presence personally. The bikes, each essentially a pair of ordinary cycles stacked into a single ride six feet high, had been in the clothing stores for less than a week when a saboteur etched a protest in acid.

"Bike Culture Not for Sale," read the runny white lettering found February 23 on the glass at the four Brooklyn Industries outlets in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

The Park Slope store's assistant manager, McKenzie Rollins, first spotted trouble when she came into work the morning before and found someone had messed with the gate locks overnight. "They looked like someone had inserted something—maybe a screwdriver—to screw them up," she says, folding a retro '80s T-shirt with a cut-out neck. "We had to buy new locks."

The next morning, McKenzie found the graffiti. "They knew it wouldn't come off," she says. "This was malicious. They could have left a note. They could have gotten in touch with us about their concerns." But who could be so enraged by using a bike to pitch hipster duds? Another saleswoman suggested something curious, that it was local members of something called "tall-bike culture."

Mutant bikers, went the prevalent speculation, had just been heard. New York's leading tall-bike gangs, Black Label Bicycle Club and C.H.U.N.K. 666, are dedicated to fashioning "mutant" bikes from discarded scraps and spare parts—for love, not money.

Among their ranks are students, professors, artists, political anarchists, and assorted white-collar types. Formed in Minneapolis, Black Label is virulently anti-consumerist; its riders recycle everything from bike parts to vegetables. They pick through dumpsters for communal vegan meals. New members join through a lengthy courting process. The less clandestine C.H.U.N.K. 666, formed in Portland, Oregon, welcomes into its fold all who express a genuine interest in building and riding mutant bikes. C.H.U.N.K. also hosts bike-building workshops for kids.

Neither club is easy to reach. Black Label's one-page website features a dated flyer for an event called "Bike Kill" and a general e-mail address.

The website of an art collective yields the e-mail address of a Black Label rider. A friend of someone in the club passes along the e-mail address and cell phone number of another. Four days pass and no one writes back or calls.

Bike culture talks back.

photo: Brooklyn Industries

A Web search turns up the direct e-mail address for "the Smelter," from C.H.U.N.K. 666's New York chapter. Finally, the Smelter—also known as Kansas—calls from a friend's funeral in Chicago. After mentioning that the club has talked it over, he gives the cell phone number of fellow C.H.U.N.K.ster Marko Bon, who goes by the name of Darko.

Who tagged the Brooklyn Industries windows? "I straight-up don't know," says Darko, sitting in a Spring Street bar. "C.H.U.N.K. is not particularly aggressive in that sort of sense." Between sips from his beer mug and with a perpetual grin, he deconstructed the depiction of all mutant-bike club members as anarchist, anti- establishment renegades.

"I'm definitely part of consumerist economy," says Darko, 30, a chisel-fea tured creative director for the Ralph Lauren website who lives in Manhattan. "I don't think that earning a living is counterintuitive to making a bike."

Darko says the primary objective of C.H.U.N.K., which currently has 20 members, is to take to the streets with people who love building bikes, and to show others they can live in an urban environment as cyclists. C.H.U.N.K's New York chapter typically rides together once every two weeks, in packs of about eight. Darko says kids sitting on the stoops in Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant hoot and holler as they pass. "There's a real energy from people when they see us ride by," he says.

Businesses hoping to cash in on the cachet of mutant bikes could never grasp the kinship of the clubs, Darko insists. "The essence of any bike group is based on the fact that when you're riding these bikes, because they are made haphazardly, they break down. So we're always stopping and helping each other fix the bikes. That's where the camaraderie comes in." The name "C.H.U.N.K." isn't an acronym but instead a reference to the pieces of tubing, machinery chains, aluminum siding, and other scraps riders weld together. The New York chapter has a work space called the Shack, near the clattering J tracks in Bushwick, where some members also live. "When you're riding a bike and somebody says, 'These bikes are great, can I buy one?' The answer has always been, 'No, but you can make one,'" Darko explained. "And if they're interested, they can come to the Shack and we can build one together."

Darko first learned of the tall-bikes flap at Brooklyn Industries stores from a private listserv dedicated to mutant-bike clubs. He said, "My feeling was, why are there tall bikes in the windows? It is so unnatural to build these bikes for any type of profit." He immediately called Brooklyn Industries' Williamsburg office to inquire about the displays.

He spoke with a woman there who put him on hold several times. "I did get the sense from them that there was this, 'Oh my God, what just happened?'" said Darko. "They didn't know what they were getting into."

C.H.U.N.K. 666: You can’t buy a tall bike, but you can build one.

photo: Marko Bon

The New York Police Department declined to comment on the case, but Brooklyn Industries' marketing assistant Allison Grenewetzki explained that employees had noted "growing chatter" about the graffiti online.

Suckapants, a blog run by photographer Tod Seelie of Bushwick, focused on the ethic of tall bikes. "Yeah, I am pretty damn suspicious of this one, especially if the bikes aren't functional," Seelie wrote after the Brooklyn Industries hit. "Then they are just decorations trying to align a commercial establishment with a piece of radical, and currently attractive, subculture."

Seelie, 27, is an avid cyclist who over the years has befriended members of tall-bike clubs through Critical Mass rides and while studying photography at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. For the last three years, he has photographed the Brooklyn chapter of Black Label.

"To use tall bikes in a window display seemed shallow," Seelie tells the Voice. "Tall-bike gangs have a very heavy base of anti-consumerism. They live in warehouses, and all their clothing could fit into a tall duffel bag. A lot of them are dumpster-diving people. The idea is to avoid consumer waste."

Seelie says he initially suspected someone from the bike gangs of vandalizing the windows, but the groups turned out to be as surprised by it as he was.

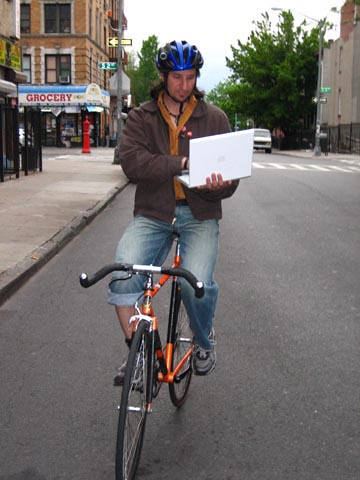

Michael Green, a film technician, filmmaker, and keeper of the BikeBlog (bikeblog.blogspot.com), also weighed in. Green, 35, who lives in Williamsburg, is a self-described fan of tall bikes who taught himself to build them in 2000 for Critical Mass rides. He says he once built a tall bike for C.H.U.N.K. "I'm not affiliated with any group but I am friends with a lot of people in those groups," Green says of his association with mutant-bike clubs.

When Green theorized on his blog that Black Label may have made the tall bikes used in the Brooklyn Industries displays, James "Stache" Mulry, a member of the New York chapter, quickly fired back.

"Black Label would never commodify bike culture," wrote Stache on BikeBlog. "In every event we have held or participated in, Black Label has encouraged the reuse of discarded goods. We have never sold a custom bicycle, nor will we ever."

IT'S ME...(bikeblog as a bikebug) Thanks Flea Billy

Soon enough, the guy who had made the tall bikes got sick of being a whipping boy for the blogs. Wayne Heller, who works on design, signs, and window displays for the company, now says point-blank, "The bikes were never intended to be sold." Heller explains that the displays were part of a charity initiative the company has forged with Recycle-a-Bicycle, which teaches kids how to make and fix bikes. According to Brooklyn Industries' website, the company gives $2 from each messenger bag it sells to the Brooklyn-based nonprofit.

Sounding like a man on trial, Heller argues that his tall bikes are rideable, even if some lack brakes. "I do not believe they should be considered unfunctional because they lacked a part that could be attached after completion," he says. Heller, a cyclist himself, took the criticism of his workmanship personally. "When we worked on these bikes," he says, "it was not meant to be commodification. It was meant to be homage."

But to the riders, that supposed homage seemed more like yet another attempt to sponge off the bikes' potential for helping to build a cool brand.

In the last few years, tastemakers have begun calling on Black Label and C.H.U.N.K. Rumor has it that Rolling Stone and MTV have asked Black Label members to cooperate for feature stories, only to be declined. Darko says magazines such as GQ, Details, and The New York Observer have contacted C.H.U.N.K., and no wonder. The club's beer-soaked signature shindig, the Chunkathalon, has one event called Flaming Bikes of Deth. It involves draping chicken wire with rolls of kerosene-soaked newspaper, adding firecrackers, then hauling the exploding rig around on a cycle. On a quieter day recently, club riders saddled up and tried to eat a hot dog at every Gray's Papaya—a mission Darko says was foiled by widespread nausea at the 11th location. They're friendly to reporters, but usually say no. "C.H.U.N.K. has no interest in commercializing bike culture," Darko says.

Some members of the mutant-bike community were understandably mystified when the Brooklyn chapter of Black Label, which normally shuns the press, agreed to be appear in B.I.K.E., a documentary directed by Jacob Septimus and Anthony Howard, and produced by Fredric King of Fountainhead Films.

The film, as yet without a distributor, chronicles co-director Howard's desperate attempts to be invited to join the gang, even as he craters into drug and alcohol addiction. B.I.K.E., set to screen at New York's Bicycle Film Festival in May, is less a definitive portrait of Black Label and more a depiction of Howard's quest. The directors give us pageantry-filled shots of Black Label riders at night, decked out in dark cut-off jackets. One member, Mesciya Lake, stares down the camera while also reveling in its gaze. "Black Label is not for the media," she says. Other riders, their faces smeared with greasepaint, engage in tall-bike jousting, a game in which two players wielding well-padded lances try to topple each other from the bikes.

C.H.U.N.K. hosts jousting too. It's fun, Darko says, but not really the point. "For anybody involved in building bikes, the joust is just a very tiny part," he argues. "It's a loud, entertaining crowd-pleaser." He is not impressed by what he sees as the "aggressive posturing" by Black Label at joint events. "That kind of behavior is for little boys. That's the wrong battle to fight," he says, adding, "The real battle is urban planning to get more people on bikes, to take back the streets, to get more bicycle paths in this city."

Around a table at the Fountainhead offices in Chelsea, Septimus and King address the contradictions of Black Label as an elite club that alternately shuns would-be members and the media alike, then lures the indie crowd through the romantic images in B.I.K.E. Septimus admits to submitting to a long, painstaking vetting process to earn the club's trust. "The film reveals contradictions, but what Black Label is ultimately saying about consumerism is, 'Do it a little less, be conscious of it,' " he says.

Septimus agrees to call Conrad, head of the New York chapter, and ask him to give the Voice an interview. He disappears with his cell phone into the next room. Several minutes pass.

When he returns, Septimus says, "They're going to vote on whether to do the interview. Conrad may reach out."

Conrad never does.

Other mutant-bike clubs, however, dispense with any attempt at cloaking themselves in enigma. Skunk, 36, called from Massachusetts to talk about SCUL, or the Subversive Choppers Urban Legion, a gleefully nerdy sci-fi-based club whose members calls their bikes "ships."

"We have a kind of rolling dance party on our bikes," he says, "where we are cheering and high-fiving everyone on the streets of Boston and ringing our bells. We'll stop and dance, eat ice cream, and go skinny-dipping."

It is Megulon Five, a leading figure for the Portland chapter of C.H.U.N.K., who strips bare the essential motivation for joining a club. He's a computer programmer and since 1992, a bike maker. "Last night, a bunch of us rode down to the river and had a few beers." That, he says, "was a little bubble of mutant-bike utopia."

send letters to the editor