Pick up the new Indypendent

If you haven't picked up the latest FREE copy of the Indypendent, there are a couple of pages dedicated to the critical mass fight.

the Indypendent is newspaper put out by grassroots, volunteer journalists from the print team of the NYC independent media center.

All people are encouraged to join up and make their own media.

more info at: www.nyc.indymedia.org

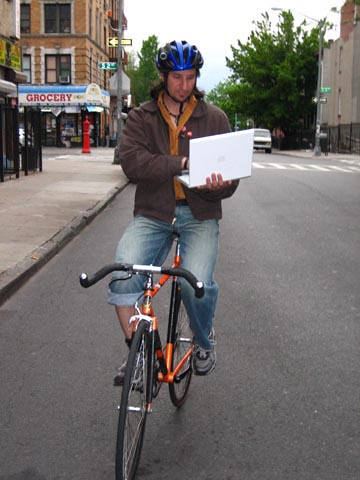

Here is one article from Chris Anderson. The cover photo seen here on the blog is from Antrim Caskey.

CRITICAL CONDITION

The whoops and hollers grew louder as thousands of bicyclists streamed from the West Side Highway through the Battery underpass. It was a warm, summer night and there were no cars, no angry SUVs, no impatient taxicabs. The 20-block-long procession had tied Midtown in knots and moved on. As the cyclists emerged from their underground echo chamber onto the FDR, they looked out over the East River and saw a full moon rising over the Brooklyn skyline.

The whoops and hollers grew louder as thousands of bicyclists streamed from the West Side Highway through the Battery underpass. It was a warm, summer night and there were no cars, no angry SUVs, no impatient taxicabs. The 20-block-long procession had tied Midtown in knots and moved on. As the cyclists emerged from their underground echo chamber onto the FDR, they looked out over the East River and saw a full moon rising over the Brooklyn skyline.

“It was amazing,” says Kaitlyn Tikkun, a regular participant in Critical Mass, the leaderless monthly ride designed to promote bike culture and non-polluting transportation in New York’s car-choked environment. “We came out onto the FDR Drive and there was a moon coming up next to us, and I looked behind me and all I could see were bikes.”

The extraordinary scene that unfolded on July 30, 2004, was the culmination of six years of rides and community organizing. Coming four weeks before the Republican National Convention (RNC), last summer’s Critical Mass rides tapped into the political energy of a city waiting anxiously for protesters and conservative conventioneers to arrive.

Over the last nine months, however, what was once a “carnival on wheels” has degenerated into an ugly standoff between the New York Police Department and a dwindling group of cyclists, who are divided over what to do next. Mass arrests and the indiscriminate impounding of bicycles are now part of the routine. In the past three months alone, there have been 85 Critical Mass-related arrests. According to New York Newsday, the NYPD devotes “significant” resources to policing the ride, with officers drawn from multiple precincts across the city.

“What saddens me is that for a lot of people whose first Critical Mass was in August [before the RNC],” says Ryan Kuonen, a Brooklyn resident and frequent participant, “they’ve only experienced the police harassment, the drama, the arrests. They’ve never seen that giant party that Critical Mass is supposed to be.”

“Surprising, Erotic, Fun”

Critical Mass began in San Francisco in 1992 as an attempt to provide an alternative to urban car culture and the marginalization of bicycle riders. The idea caught on, arriving in New York in 1998. Critical Mass (criticalmassrides.info) rides now take place on the last Friday of each month in over 300 cities around the world. The Manhattan ride begins at 7 p.m. on the north side of Union Square Park. Chris Carlsson, one of the founders of Critical Mass, describes the early days of the ride as “exuberant, surprising, erotic, fun and utterly transformative.

“No one knew what to expect,” Carlsson adds, “and no one anticipated just how amazing and fun and open-ended it would be.”

“Critical Mass,” Ryan Kuonen states flatly, “is the most exciting thing I’ve ever done. It’s a carnival on wheels, and I love it.”

Some participants laud the ride’s transformative effect. “For a lot of the new people who join the ride, Critical Mass is fun,” says Bill DiPaola, a volunteer with the environmental group Time’s Up! (times-up.org) which helps promote Critical Mass in New York. “When people come on the ride though, they get a sense of freedom that they’ve never gotten before. They realize that you can ride a bike in New York safely. By the time folks get off their bike they start think about riding it to work, using it more and fighting to get changes in the infrastructure of the city that will make riding a bike in New York a safer experience.”

DiPaola is convinced that the growth in the popularity of bicycling in New York City has occurred despite the city, rather than because of it. “Manhattan is a flat city, and riding a bike here makes a lot of sense,” he says. “The problem is that riding a bike here is also incredibly dangerous. Critical Mass is one of the things people can do in New York that both lets them ride a bike safely and also makes a statement about where we think the city’s priorities should be.”

By early 2003, after five years of Critical Mass, rides were drawing several hundred participants. While police on scooters would often accompany the ride, it was largely accepted and even ignored by city officials. The popularity of the ride grew tremendously throughout the summer of 2003, thanks in large part to a well-publicized “Bike Month” that ended with a Critical Mass attended by over a thousand bikers. That October, more than 2,000 cyclists thronged the streets for a Halloween night ride.

More than 2,000 bicyclists also turned out for the July 30 ride that took over both the West Side Highway and FDR Drive. “That night,” wrote Dave Bonan on the nyc.indymedia.org web site, “the cars were driving on our road.”

Warning Signs

However, the July ride witnessed the first signs of more stringent policing. “In July it started to feel like the police were practicing for the RNC,” says Ryan Kuonen. Scooter cops zoomed to the head of the ride, blocking cars on ramps from entering the highways dominated by bicyclists. Meanwhile, unmarked police cars tailed the ride, threatening to arrest cyclists who were similarly “corking” traffic.

During the Aug. 27 pre-RNC ride, 264 bicyclists were arrested; the arrests have continued ever since.

Following the aggressive police response, Bicycling advocates turned to a legal strategy to secure the ride. On Oct. 19, five bicyclists filed suit against the NYPD alleging that the police illegally seized locked bikes during the September Critical Mass ride. In response, the city counter-sued, asking a U.S. District Court on Oct. 26 to permanently enjoin anyone from riding in Critical Mass without an official permit. Although the suit was tossed in late December, the city refiled it in mid-March. This time the city not only sought to block the ride but also to enjoin DiPaola and four other Time’s Up! volunteers from personally promoting or even talking about the ride.

“The city’s argument is very troubling,” noted veteran civil rights attorney Norman Siegel. “It’s a prior restraint and a violation of the First Amendment. It’s clearly unconstitutional. If the city prevails, social justice activists could not publicize the gathering of people to engage in any form of civil disobedience.”

Outside the courtroom, activists have fought back in other ways, filing a Freedom of Information Act request to find out exactly how much the city is spending on policing the ride. Critical Mass riders have responded by launching the ride from multiple points across the city and using text messaging to avoid the police.

Police tactics have been aggressive. According to NYC Indymedia reports, the NYPD has deployed scooter squads, uniformed and plainclothes officers on foot and bikes, orange netting, marked and undercover vans, loudspeakers, command units, video surveillance teams and helicopters in response to Critical Mass. In court testimony related to the lawsuit against the Time’s Up! volunteers, Assistant Police Chief Bruce Smolka noted that the NYPD devoted “a large amount of resources, personnel and equipment” to the monthly rides.”

Many believe that Critical Mass participation has suffered as a result. “The ridership this spring has been way down,” says Kuonen. “Normally by this time of year you’re getting rides of 300 or 400. April’s ride was barely 150. Maybe it was the weather, but I don’t think so. I think the police tactics are working.

DiPaola admits that some of the pageantry and excitement of Critical Mass has been drained by the police. “The city has stripped the ride of families, of color, of people performing, of people on tall bikes, on artistic bikes. That’s for sure. But we also feel that the bike has survived the winter in the face of massive police intimidation and corruption.”

Selective Enforcement

With attention focused on the Critical Mass battles in Manhattan, the NYPD’s selective enforcement policies have been largely overlooked.

The same city administration that sued Time’s Up! members to keep them from talking about Critical Mass has itself spent tens of thousands of dollars funding New York City Bike Month calendars that publicize the ride.

The calendar, published by the bike advocacy group Transportation Alternatives, lists the May 27 ride as a “Bike Month” event. “The Bike Month calendar listing Critical Mass did receive funding from the city,” acknowledges Dani Simons, event director for Transportation Alternatives. Clearly trying to distance Transportation Alternatives from the controversial ride, Simons adds,”the listing for Critical Mass is only one of over 150 bike-related events this month, and I guess we’d just see that as confirmation that Critical Mass is only a small part of the New York bicycle scene.”

The city has also been less aggressive in policing the Brooklyn Critical Mass. Although most riders acknowledge that there are often as many police (one to two dozen) as people on the Brooklyn rides, there have yet to be any arrests at the outer borough event, which occurs on the second Friday of every month, beginning at Grand Army Plaza.

“The police there seem really intent on getting us to agree to certain guidelines ahead of time,” says Kuonen. “But once the ride starts, even though they follow us, they’ve never actually arrested anybody.”

Looking Ahead

With the future of Critical Mass in New York City hanging in the balance, participants are debating how to save the ride.

Bicycling activists are hopeful that the political winds are shifting. “Politicians are starting to come out in support of Critical Mass, community boards are voting to support us, the artistic community is rallying around us,” says DiPaola. “We feel like the only people in this city who don’t support Critical Mass are the mayor and the NYPD.”

“Time’s Up! will never ask the city for a permit for Critical Mass because it’s not our ride,” he adds. “We don’t sponsor it, no matter what the city claims, and we couldn’t ask for a permit even if we wanted one.”

Many riders have begun launching Critical Mass from multiple points around Manhattan, a tactic recommended by Chris Carlsson, a veteran of San Francisco Critical Mass’s struggle to stay on the streets in the mid-1990’s. “Remember,” said Carlsson, “it’s not illegal to ride your bike, so we can always fall back on that.”

Other riders have taken the opposite approach, urging participants to obey traffic laws. “What if we didn’t blow stoplights?” asks Critical Mass participant James Bachhuber.

For her part, Kuonen sees promise in the Brooklyn Critical Mass. She’s actively working to increase knowledge of and participation in the event, and hopes that it can remain mostly trouble free.

“I think that if George Bush had never come to the city we would never have had this problem,” she said. “The police told us we couldn’t ride, and we did anyway, and now it’s just a big power play. But no matter what happens,” she added, “we have to get Critical Mass back to what it’s supposed to be: fun.”

(Matt Wasserman and A.K. Gupta contributed to this report.)

The Manhattan Critical Mass will be held on May 27 and June 24. The next Brooklyn Critical Mass will be June 10.

1 Comments:

nice post

football merchandise fan club shop

Post a Comment

<< Home