article on DC messengers

Article on DC messengers from Knight Ridder:

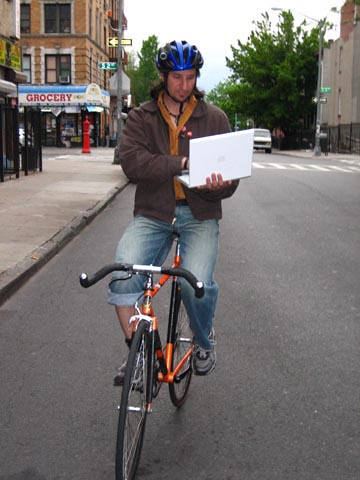

Capital bike couriers ride hard, drink hard, crash hard

By Banks Albach

Knight Ridder Newspapers, November 7, 2005

WASHINGTON - When Jason Harper came to, his roommate was shaking him,

asking why his face was a bloody mess.

"I didn't think it was that big of a deal," Harper, 29, said of what

proved to be facial abrasions and a concussion. "I've gotten plenty of

concussions before."

The last he remembers, he was zipping through downtown Washington,

racing his bike against time and traffic. He's a bicycle courier - one

of several hundred free spirits who, whether in sleet or steamy summer,

make deadline deliveries in the famously impatient capital. Some smoke,

others chew tobacco and most drink - heavily. More wear tattoos than

helmets. Few have health insurance.

The faster they ride the more money they make. The companies they work

for charge clients zone-based rates that start at around $6 for

delivery within one hour. For rushes and after-hour deliveries, fees

double. For double rushes, they triple. Couriers pocket about half the

fee.

"One-hour local is insulting," rider Chris Brown said. "Double rush

gets the adrenaline going."

"On a good day it feels like flying," said Dana Heater, 31, a five-year

courier with a large forearm tattoo and a nose ring. "It's like we're

the only people in the city and everyone else are obstacles. It's

really a dead-end job, but it's beautiful."

A courier might pocket $200 on a busy Friday, less than $80 when it's

slow. Impressing the dispatcher helps. Dispatchers deal out the

juiciest jobs to the fastest riders or favored ones.

As independent contractors, couriers set their own hours. But that

freedom stings when they face serious medical bills. Like Harper, most

walk away from accidents and lick their wounds on their couches.

When it comes to taxes, "Everybody has their own idea," said courier

Brian Petit, 25.

Because time is money, many couriers tweak their bikes for speed. Hans

Scheltema, 31, a veteran rider who pulls in around $40,000 a year, saws

his handlebars to the width of his waist to squeak by side-view

mirrors.

"I don't want to do anything else. Even when the weather's crappy it's

great," Scheltema said in a cell phone interview.

A squawk interrupted the conversation. "Let me call you back. My

parrot's getting p-----," said Scheltema, explaining that the parrot,

Pookie, who can say only "Hello, how are you?" and "10-4," bites his

neck and ear when vexed.

Motorists know couriers best from the red lights they run. Bikers call

it "shooting the hole" or "cutting the gap." Instead of looking for

cars, they look for where they aren't, several explained.

"We know the light cycles," Heater said. "I know when to slow down or

speed up."

She and many other couriers ride track bikes, which have single fixed

gears and no brakes. Riders stop them by leaning forward over the

handlebars and pressing back against the pedals, which locks up the

wheels.

"I've seen people who can stop those things on a dime, but that takes

amazing skill," said Sheba Farrin, 32, a veteran messenger.

Track bike riders say the secret's simple: Don't stop.

Even the fastest couriers will never beat e-mail, which has hurt the

industry nationally. But the capital's couriers have a unique

advantage: Washington's a city of deadlines, whether it's for court

filings, Securities and Exchange Commission reports or lawmakers

awaiting Wizards tickets from lobbyists.

Sometimes riders schlep personal items, too, such as umbrellas,

forgotten laptops, Chinese takeout, hockey sticks or even, in one case,

a set of golf clubs. One courier said he returned a little black book

that conservative pundit Robert Novak had forgotten.

Counterterrorist measures are worse obstacles than e-mail. Several

riders recalled the pre-9-11 days of the "Capitol Hill multiple," when

they could personally deliver their goods to every member of Congress,

collecting a fee for each. Now they must leave all their packages for

lawmakers at one stop - a security trailer at the base of Capitol Hill

- and collect only one fee.

At the end of the day, couriers march into saloons in their jerseys and

bike spike shoes, toting their massive bags. Jell-O shots are a

favorite: paper cups full of Jell-O made with vodka.

Kim Reynolds, 31, gobbled down one, which was nearly the same color as

her electric pink hair, and explained the hazards of her work.

"With concussions, you go into shock," she said. "For 20 minutes before

and 20 minutes after you don't remember" anything.

She doesn't remember hitting her head in a crash in August, for

example. She does remember waking up surrounded by people looking down

at her.

"That was the funny part; these people looked horrified," Reynolds

said.

2 Comments:

Bikes are always been my game and i love pocket bikes alot

dont drink and ride bike... it is dangerous

Codeine Cough Syrup

Clonazepam vs Xanax

tips malam pertama

malam pertama

malam pertama pengantin

kisah malam pertama

cerita malam pertama

pengalaman malam pertama

cerita lucu malam pertama

madu khaula

percocet 5 325

vicodin 5 500

antique bird cages

maytag dishwasher parts

headboards for queenbeds

ge dryer parts

ge dishwasher parts

ativan vs xanax

klonopin vs xanax

lorazepam vs xanax

zoloft weight gain

phentermine results

nexium coupon

advantix for dogs

Post a Comment

<< Home